“Apologetics, if it’s not undergirded by love, it’s really nothing more than a sword intended to decapitate the person in front. That’s not what apologetics is about. It has to be undergirded by love.”

I listen to several different theology podcasts, and I recently discovered Ravi Sacharias, a scholarly, compassionate and up-to-date apologist. He is Indian-born and Cambridge-educated, and he gives the most compelling and

relevant critiques of contemporary thinking and current world events I have come across. He runs RZ International Ministries,

and speaks around the world.

This is a transcript from his ‘Just Thinking’ podcast,

part of a four-part series titled ‘If The Foundations Be Destroyed’.

“Many years ago, it was [Orval] Hobart Mauer, who at the age

of 65 committed suicide. He was a PhD from John Hopkins, one-time instructor at

Yale, one-time professor at Harvard; in 1974 he was the president of the

American Psychological Association; at the age of 75, ultimately took his own

life. He said, well before he died, that the one article he wrote in the

psychology magazine at that time [‘Sin, The Lesser of Two Evils’, American Psychologist, 15 (1960): 301-4],

brought more hostile response than any other thing he’d ever written. Even though

he was a sceptic himself on matters of God, he wrote this:

‘For several decades, we psychologists have looked on the whole matter of sin and moral accountability as a great incubus and have claimed our liberation from it is epoch-making. But at length we have discovered to be free in the sense that is, to have the excuse to be ‘sick’ rather than to be ‘sinful’, is to court the danger of also becoming lost. This danger is, I believe, betoken by the widespread interest in existentialism, which we are presently witnessing. In becoming amoral, ethically neutral and free, we have cut the roots of our very being, have become lost in our sense of selfhood and identity, and with neurotics now find ourselves asking, ‘Who am I? What is my deepest destiny? What does living really mean?’. When we lost this vertical dimension, we lost the idea of who we are and what living really means.’

But I remember it was in Damascus, and being hosted by

Daniel, and being asked to talk to one of the leading Shiites, cleric Hosein.

And we had a three-hour conversation, as he was one my right, between us was

the interpreter, and the audience in front of us. No hostile attitude. Just a

cordial discussion on our differences, and it went thus: he would ask me one

question about the Christian faith, I would have to answer it; I would him one

question about the Islamic faith, he would have to answer it. And there was not

one ill word spoken. He was a very gracious man, always respectfully addressing

me as ‘Professor’, ‘Professor’, ‘Professor’.

And after that three hours of discussion with Sheikh Hosein,

the leading Shiite cleric in Damascus, he looked at me across the interpreter

and she interpreted, and he said, ‘Professor Zacharias, maybe it’s time

for us in the Muslim world to stop

asking ‘If Jesus died on the cross…’ and to start asking ‘Why?’’. I said, ‘Sheik

Hussein, can I quote you on that?’, he said, ‘Yes, sir’.

It’s time for us to start asking ‘Why'.

As men like him are probably looking out the window and

seeing lives slaughtered, and men women and children just mangled on the

streets for political theory all over again, I wonder whether he is thinking

now himself of the cross as the only answer for the evil that is in the heart

of men, for forgiveness, for grace, for transformation.

To those of you who are studying here, I want to challenge

you with this. No matter where you defend the faith, no matter where you

present a defence of the Christian faith, never end without telling them about

the cross. Never end without that.

Because at the heart of the gospel, is precisely that

message: that your heart and my heart are desperately wicked. And the Son of

Man came to this word to seek and to save that which was lost, to offer you and

me that forgiveness, and that grace, and that cleansing, and the imperative of

transformation. This is at the heart of the gospel message.

That’s why Bilquis Sheikh,

the convert from Islam in Pakistan, writes the book, ‘I Dared To Call Him Father’. Because suddenly they understand that forgiveness is a gift,

unearned.

I’ll give you this story and then move to my final thought

here.

A few months ago, I was in Jerusalem, and I was hosted by

four Palestinian young men in a quiet setting for lunch. Very fine young men.

One of them was a product of our Oxford program. The guy sitting next to me, he

said to me,

‘Ravi, can I tell you a conversation I observed, watching Brother Andrew talk to a Muslim cleric? I was an observer, I didn’t say a word, I saw Brother Andrew talking to this man, who had ordered to death of eight Israelis, because the Israelis had killed four Palestinians, and this Sheikh had ordered the killing of eight, two for one. And as Brother Andrew was talking, I was listening. Brother Andrew looked at this man and said, ‘Who made you the executioner of the world?’ And the man said ‘I’m not an executioner, I’m an instrument of God’s justice’.

Brother Andrew leaned forward and said to him, ‘What then of forgiveness? What place does forgiveness have?’ And he looked at Brother Andrew, didn’t blink an eye, didn’t bat an eyelid, and he said, ‘That's for only those who deserve it.’’

You and I are accountable. We are accountable before God.

And there’s a cross offered for you and me for redemption, and for the daily

reminder that but for his grace, we would be condemnable also.

Eternity, existence.

Morality, essence.

Accountability, conscience.

And lastly, the dimension of charity, beneficence.

And I just close with this. It is very easy in our time, very easy in our time, to get angry with opposition. You look at those who seek to eradicate what we believe, and that anger wells up within you. We were having a nice conversation over breakfast with a few students, and we were chatting. You know, apologetics, if it’s not undergirded by love, it’s really nothing more than a sword intended to decapitate the person in front. That’s not what apologetics is all about. It has to be undergirded by love.

And I just close with this. It is very easy in our time, very easy in our time, to get angry with opposition. You look at those who seek to eradicate what we believe, and that anger wells up within you. We were having a nice conversation over breakfast with a few students, and we were chatting. You know, apologetics, if it’s not undergirded by love, it’s really nothing more than a sword intended to decapitate the person in front. That’s not what apologetics is all about. It has to be undergirded by love.

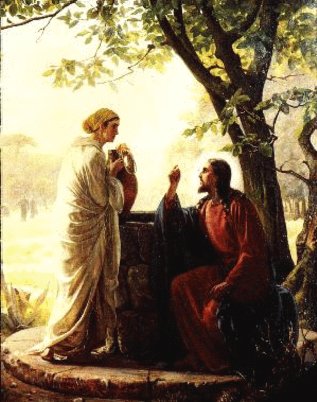

I like the way our Lord handled the woman at the well. So

gently. So graciously. So that she runs back and says, ‘Come and see the One

who knew everything I had done. The Messiah has come.’ There is the gift of

love in the gospel. And one of the main reasons the church suffers today,

often, is that we have not even displayed that love to each other, leave alone

to the world. Not even displayed that love to each other, leave alone to the

world.

If we are going to win this, we are going to win this with

the conquering disarming power of the love of Jesus Christ.

Two, three years ago I was in Dehli, where I grew up until I

was twenty. I was born in the South, and raised in Dehli. I used to go downtown

with my buddies, and we’d go and see the movies or have a coffee or something

like that. And I was walking past the Regal Theatre in Dehli, and I saw a man

lying on a little box, a little square piece with four wheels. One leg was gone,

the other leg was bandaged up. Pretty messy looking stuff. And he was wheeling

himself. Somebody obviously brings him every morning, picks him up every night;

he’s obviously not alone. And as I was walking along I was about to stop and

put some money into his hand. […] And he made a turn into a street where there

were not too many people. And I stopped, got on my haunches, took his hand – it

was a bit of stump – and I took his hand, and I held a hundred rupee note,

which is a lot of money for him, it’s two US dollars for me. So I opened it,

put that hundred rupee note in his hand, and just clasped it. And he just looked

at me and in Hindi he said to me, ‘Sahibji’ (Respected sir: Sahib, Ji for reverence),

‘Sahibji, may the self-existent one God richly bless you’. And in Hindi I told

him, ‘I come to you in the name, and with the love of Jesus Christ. This is his

gift to you.’ I tell you what, you can’t capture the expression.

The love of God. The eternal. The moral. The accountable. And the charitable.

Those are the foundations. Life is not gratuitous and

purposeless. It’s built on the foundations of an eternal God, who revealed to

us the moral law, and reminded us of how we had fallen, and with love reached

out to us again, to bring us back to Himself.”

Let's pray that our witness of God's love and forgiveness may be prompt for them to come to Him.

- Ravi Zacharias

How can Christians live out love in the face of violence from our Muslim cousins? Here is an interesting answer to that question, emphasising perseverance, and the concept of 'witness always, speak if you must'.

Ravi's lecture reminds me of the beautiful painting by Normal Rockwell, which is entitled according to Golden Rule, the unique mandate given to us by Christ, to positively engage in active love toward others - a mandate not equalled by Buddhism (consider others as yourself - passive and thought-based) nor by Taosim (do not do unto others as you would not have done unto yourself - refraining from negative acts). We are to love each child of God, whether Jew or Gentile.

No comments:

Post a Comment